One major topic I want to explore is “missing middle” housing in the Boston area. The term was coined by Congress for the New Urbanism member Daniel Parolek to describe the typologies in between single family houses and double loaded corridor midrise apartment buildings. This includes duplexes, triple deckers, quads, townhouses, live/work buildings, etc. These residential types were widespread in every American city before suburbanization and zoning. They meet an important need for less expensive market rate housing since they are very efficient and have lower construction costs per square foot than larger buildings.

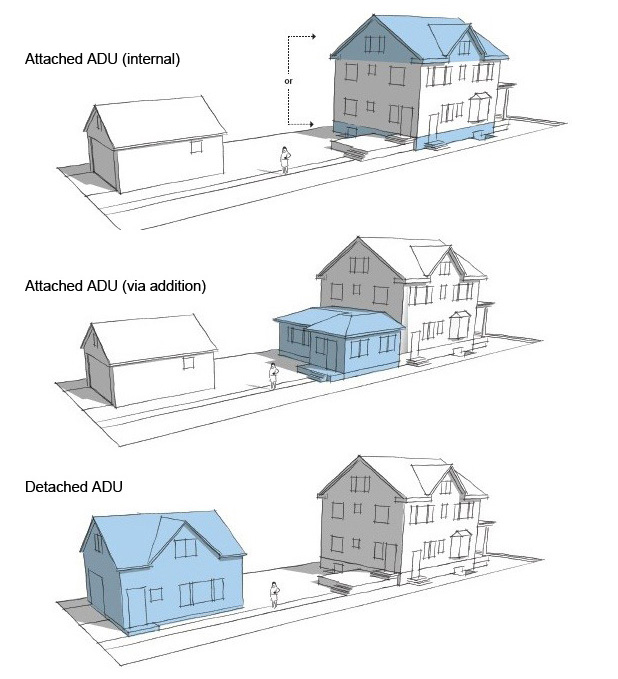

I am going to start with Accessory Dwelling Units, also known as ADUs, because the city has the opportunity now to craft some meaningful policy. ADUs are smaller housing units which can take the form of an apartment in a larger house or a tiny detached building in the yard. Full disclosure, I’m recycling some material from my MIT thesis.

Legalizing by-right ADU construction is possibly the most impactful change the city can make to its housing policy to create naturally affordable units in the mid and low density neighborhoods. It has the benefit of preserving the current (relatively) affordable housing stock and adding more new units at low price points, making the supply of housing more elastic. If you’re allergic to economics scroll to the next section.

Real estate in Boston currently suffers from regulatory scarcity, where rigid zoning, laborious permitting processes and high land cost per unit make it difficult to add housing in many neighborhoods. The supply of real estate here is inelastic: the city grows more slowly and prices go up faster than they otherwise would in an unconstrained market.

The above charts show increased demand for residential real estate with an elastic supply, such as in Austin, Texas (EoS = 3.0) and an inelastic supply, like Boston (EoS = 0.86). The supply curves are kinked at the old equilibrium point because housing is a durable good and units don’t immediately disappear if demand goes down. What happens above the old equilibrium point at the new demand curves depends on the elasticity of the housing supply. With an elastic supply, more units are easily added to the market with smaller price increases. A 10% increase in housing units would result in prices going up about 12% in Boston but only 3.3% with Austin’s elasticity. That’s literally the difference between rent going up $120 a month and $33 a month with the same population growth. If Boston wants to keep the rent from getting even more out of control it needs to allow the real estate market to get more elastic. The city’s first ADU program unfortunately didn’t have that effect.

Boston Barely Tried ADUs

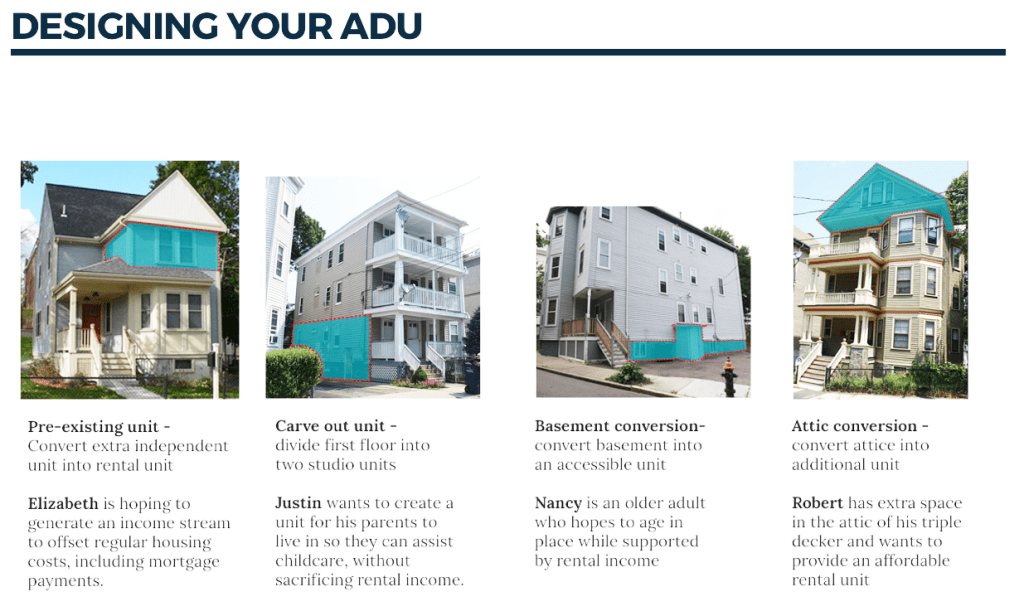

On November 8, 2017, the Mayor’s Housing Innovation Lab and ISD passed the Boston Additional Dwelling Unit 18-month Pilot Policy to “allow owner-occupants to carve out space within the envelope of their home for a smaller, independent rental unit.” The purpose of this pilot was to increase affordable housing options, support multi-generational family arrangements, and legalize informal rental units.

The eventual policy was the culmination of a long public process, and though the original proposal included various types of accessory dwelling units, the final policy was only implemented in Eastie, JP, and Mattapan, and it specifically prohibited building any additional square footage. I’m ecstatic that the city was willing to try ADUs, but this prohibition really killed the pilot.

The pilot got 55 applications in that year and a half, but only 12 ADU permits were issued. Ten of them were basement apartments. Overall, this is a pathetic number for a typology with so much potential. There were approximately 288,716 housing units in the City of Boston as of 2018, so 12 additional units is +0.0042%, basically a rounding error. A dozen new units won’t move the needle for average rents. The Metropolitan Area Planning Council estimates that Greater Boston needs more than 400,000 additional housing units by 2040, so 8 affordable units per year is a drop in the ocean.

Let’s turn to look at the success of accessory dwelling units in places that have approached their development more aggressively.

The Urban Land Institute’s ADU Study

As shown in other parts of the country, ADUs can be a relatively simple and effective tool for adding housing in moderate density neighborhoods. In 2017, the Urban Land Institute (ULI) published Jumpstarting the Market for Accessory Dwelling Units: Lessons Learned from Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver. The report is a comprehensive study of ADUs in the pacific northwest’s major cities and it’s by far the best source I’ve seen on the subject. In these areas, many homeowners have welcomed the ability to add new ADUs. The units provide extra bedrooms or serve as home offices, and can bring in additional rental income. For relatively low construction costs, most new ADUs are unsubsidized, have below-market rents, and add new housing units to the market.

The report says that across Portland, Seattle and Vancouver, 67% of ADUs are detached, with some above garages or within former garages. Just 4% are carved out of the main house, 12% are in basements, and 11% are attached garage structures. According to these numbers, only 27% of these ADUs would be allowed with Boston’s current policy. Of the three, Portland most aggressively promotes ADUs, with no owner occupancy requirements, no design reviews, as of right zoning, and waived fees.

The average surveyed ADU development cost in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver was approximately $156,000, including a significant standard deviation of 76%. This variance exists because some houses simply need modifications like a new wall or two and an exterior door to carve out an ADU, while other units become extravagant new guesthouses. Typically ADU costs per square foot are close to multifamily new construction costs. However, the difference is that ADUs usually have less square footage, better net to gross efficiency, don’t include a developer profit, never have underground parking, and the land is almost always free. Additionally, cities can lower ADU costs by easing the permitting and zoning requirements and reducing development fees.

In the ULI Report, rents for average ADUs in the three cities were around $1,298 per month with a standard deviation of 47%. Most ADUs had one occupant (57%) however some had two (36%). Interestingly, the largest share of ADU residents (46%) were renting at an arm’s length transaction, while about a quarter knew the landlord and were likely getting more favorable rates. Since many homeowners wished to change the use of their ADUs over time, regulatory micromanagement was generally unwanted.

Most ADUs (40%) used funds borrowed against primary house equity, however, some (30%) were financed with cash and a few (4%) borrowed against the future value of the ADU itself. When loans are obtained, local sources are critical because they know the intricacies of the municipal ADU regulation. With a better loan system, ADU construction could be attainable to the less affluent and provide even more affordable housing.

Most of the surveyed homeowners were prompted to build their accessory dwelling units by the new ADU zoning (42%), a recent cash influx (19%), seeing ADUs promoted (15%), or having a neighbor build one (8%). The most important zoning reforms were reducing minimum lot sizes and increasing allowable floor area, which Boston failed to do.

Of the total applicants in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, only 19% were turned down for permits, and approximately half were fixed with design tweaks. Constructing ADUs was very fast compared to typical home construction, with most taking 6-18 months from soup to nuts, versus three or more years for larger homes. In Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, transparency and predictability were most helpful for permitting. Additionally, professionals with local ADU knowledge made the process easier, and local pamphlets on ADU construction from the cities were appreciated.

ADU Policy for Boston

Though the pilot policy worked toward reducing illegal dwelling space and incentivizing more home-sharing, it missed out on the greater opportunity to add significantly more housing. If the Boston ADU market behaves similarly to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, allowing ADUs with additional square footage could lead to a large increase in applications. Small courtyard homes in Europe show that even the densest areas can accommodate tiny units. Homeowners should be encouraged to build! The city says it wants to expand the ADU program after analyzing the results of the pilot, but I am worried that it won’t go far enough. Boston should permit as many ADUs as possible if it wants to be an inclusive city.

Regulations should be reduced and the permitting process should be simplified as much as possible. As of right allowances for certain increases in square footage or the replacement of exterior sheds and garages can further reduce the cost of ADU construction, making it financially viable in areas of the City where rents are low. Occupancies should be allowed to change over time with minimal regulation. And, in order for ADUs to be financially attainable, local lenders should be educated to make small loans so that ADUs aren’t only built by those with cash or substantial housing equity.

Based on the ULI report and construction costs in eastern Massachusetts, a 500 square foot ADU could be built custom for $300 per square foot, or $150,000, in less than 18 months. This represents approximately half the total development cost in half the time of an income restricted unit in a multifamily building. Prefab can potentially be even cheaper and faster. James Shen’s modular Plugin House was exhibited outside Boston City Hall in 2018, despite being illegal to build under current zoning. It could be very inexpensive if manufactured in bulk, and the walls go up in just a few hours. But we don’t even have to look at hypotheticals; you can actually buy a decent 540 square foot tiny house kit on Amazon for $32,990 right now! (It will take two people a week to assemble it, but that’s small money, call it $7k of labor.) Whether they cost $40,000 or $240,000, ADU construction should take off.

Here are quick and dirty pro formas for market rate and affordable ADUs in Boston. The high end unit assumes custom ground up construction and market rate rent in a neighborhood like JP. With solid rents and low development costs, the IRR calculations I did look really good. For the low end ADU I am assuming a kit house or prefab unit, and I’m pushing the rent as low as possible to show that ADUs can provide truly affordable housing with no subsidy. They won’t make much money with rent so low, but these units would be perfect for many people from senior citizens on a fixed income to the formerly homeless. Allowing units like both of these ADUs should be a no-brainer.

I know I’m being hard on Boston. Local politicians need to try and make everyone happy, including the homeowners who want their neighborhoods to be frozen in the 1970s, but the rent is getting too damn high. We need more inexpensive housing. Luckily, NIMBYs don’t have that much to complain about with ADUs, since they’re either built within or added onto a main house, or are not much larger than a detached garage. One common issue is parking, but I’ll get to that later…

To reiterate, ADUs deserve serious attention because there are few ways to build affordable housing units so inexpensively and quickly in Boston. Old, rotting garages and under-utilized patches of dirt in the residential neighborhoods represent thousands of potential sites for new ADUs.

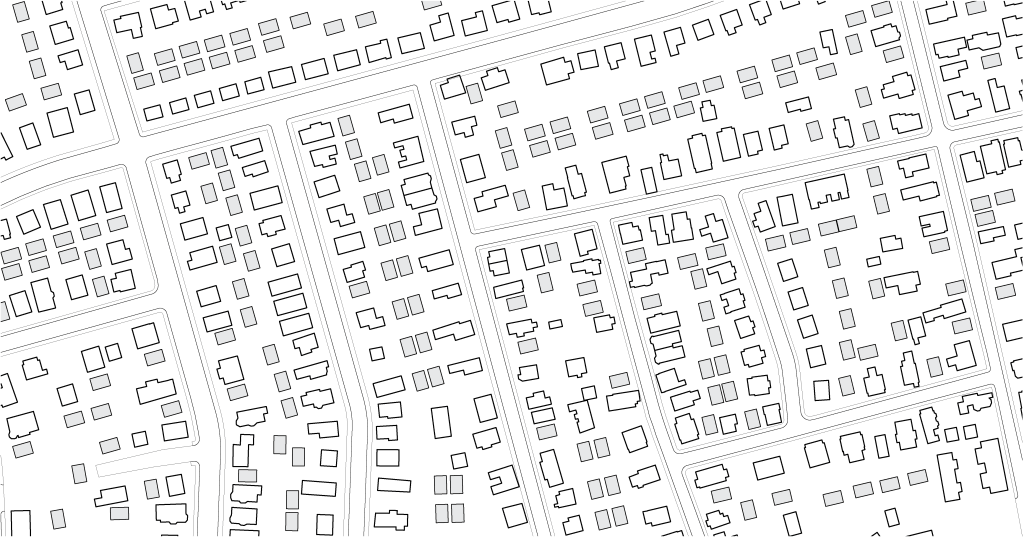

Exactly how many new ADUs the city could accommodate is difficult to gauge, but its easy for me to imagine that there’s space for tens of thousands of them around Boston. The city is 48.4 square miles, or 30,976 acres, with 37.7% of that being classified as residential, which is 11,678 acres. That means the city averages roughly 25 dwelling units per residential acre, a relatively low number. Some neighborhoods, like the North End, have blocks with 100-200 dwelling units per acre. Adding several ADUs per acre on average should be no sweat, but I don’t have the patience for a better estimate. Realistically, 15,000 would be a solid goal, for a city-wide dwelling unit increase of about 5%. Trees obscure a lot of the vacant land on satellite images, so the city’s CAD file makes it easier to see how much space many homes are swimming in.

In this brief exercise I found space for 175 new, single story, 20’x30′ (600 square foot gross) detached ADUs in this 34 acre section of Mattapan, for a rough unit increase of up to 50%. Not every block has enough backyard space for this, but I think the potential in areas like Mattapan, West Roxbury, Roxbury, Dorchester, JP, Cambridge, Somerville, etc. is clear. These short and minimally invasive structures would hardly change the “character” of the neighborhoods at all. If it looks like I’m packing them in here, please keep in mind that even with all these proposed ADUs its still one of the least dense areas of the city. The lots in this area are all one, two, or three family, and most are 4,000 to 6,000 square feet. I share a 1,800 square foot lot with twenty other people and I’m happy as a clam. No one has to build ADUs, owners will only do so if it makes sense. I bet less than a quarter of the ones I drew would get built, and that would still be a win. There is no valid health and safety reason for banning ADUs that are built to code.

Keep in mind, old school ADU-like units exist all over Boston. You’ll find garden level apartments in some of the fanciest brownstones, backhouses in the North End, converted carriage houses in the Victorian neighborhoods, and cottages or small apartments in houses further from downtown. Many were built when the city experienced massive population growth during the second half of the 19th century. We have a similar housing crisis now, and ADUs should be an important part of the solution. But we’ll need a policy that permits more than a dozen to be built. I don’t think ADUs will solve all of our problems, but they could go a long way.

I personally lived in an ADU for a summer in Pennsylvania and have wonderful memories there. Plus, the price was right. Boston, please allow this important type of housing to proliferate. □

I want to give some credit to Phil Cohen, who I coauthored my thesis with. Thanks, Phil.

Additional Sources

https://accessorydwellings.org