Everyone loves charming historic storefronts with cozy apartments above. It’s a big part of why people gravitate to traditional urbanism. This is what Charles Street, corner stores in the North End, and Jane Jacobs’ Greenwich Village are all about. It’s nice being able to pop out of your home and have quick access to goods and services. The pedestrian realm is much more interesting when it’s lined with local businesses. And it’s great to get to know the people. Without neighborhood retail it’s harder to develop an urban community.

So, with the tremendous growth that Boston has seen in the past decade, why are so many of the city’s retail spaces vacant? Why have historic storefronts been bricked up and converted to dingy studios? How come there are so many streets in expensive neighborhoods that look like the economy hasn’t done well at all?

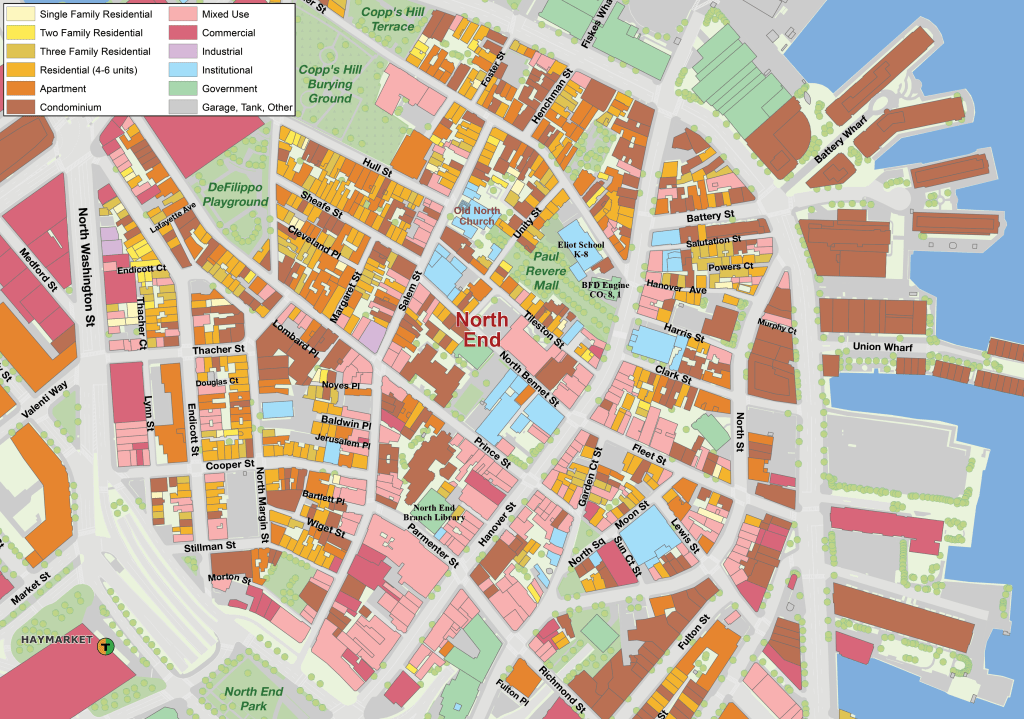

There are many such storefronts (100-600 square feet) in the older Boston neighborhoods, including the North End, Beacon Hill, Chinatown, the South End, Roxbury, and Cambridge. As many as two thirds or three quarters are bricked up in some areas. Inferior brickwork and visible steel lintels give them away. Aside from streets that city planners have designated as commercial corridors, such as Newbury, Charles and Hanover streets, almost all of the historic storefronts are gone. They are either empty, converted to tiny studios, or incorporated into other ground floor apartments.

The storefront at the far left has already been bricked up and incorporated into another apartment. Image by Nishan Bichajian at MIT.

It would be nice if more of them were still retail, but in many respects there is an oversupply of small historic storefronts. Most of these spaces were built by the first half of the 20th century when the tenements were packed, everyone had to shop locally, and there were no large stores.

Boston suffered from population decline in the last century, as the city went from 800,000 in 1950 to 560,000 in 1980. It is now back up to just 700,000, and that growth occurred in some neighborhoods much more than others. Historic districts have seen further depopulation as the tenements became less crowded, the city-wide average household size shrank from approximately 3 to 2, and few new units were added in these neighborhoods, which reduced the demand for goods and services even more.

The mid and late twentieth century also saw the consolidation of family businesses into large corporations and the advent of modern supermarkets and malls. The physical retail climate got worse again in the 21st century with the growth of online shopping, further reducing demand for local retail. The West End Whole Foods market is approximately 20,000 square feet, meaning it contains the same square footage as dozens of smaller storefronts, which often aren’t even compatible with 21st century businesses.

The housing crunch is also driving up residential rents, and with the difficulty of developing new space in downtown’s historic districts, any available square footage is being gobbled up for apartments. In many cases residential prices can surpass commercial rents for the same space.

Real estate taxes are another factor, with a commercial tax rate that is approximately 2.5 times the residential rate. In 2020, it is $24.92 vs $10.56 per thousand dollars of value.

And then there are the NIMBYs. The Not-In-My-Back-Yard neighbors who tolerate or even love existing mixed use but fight any new businesses out of fear that they could negatively impact them in some small way. Many yell and scream about historic preservation, naively or selfishly ignoring the fact that these neighborhoods historically were much more crowded and had many more ground floor businesses.

So we are left with the status quo, where ground floor retail is squeezed out.

The Fates of Four Ground Floor Storefronts

The intersection of Phillips and Grove Street, a rare orthogonal grid intersection, provides an interesting natural experiment with four nearly identical corner stores. They are all of similar vintage, circa 1880-1915, and all have classic corner entrances with cast iron columns (they are wonderful architecturally, but these older designs aren’t great for accessibility). Each space has fared differently.

One storefront was poorly bricked up and incorporated into a ground floor apartment. Another was converted to a studio, although the old storefront was rebuilt with a decent design that both works for residential and is true to the original corner store condition.

The next is now Beacon Hill Yoga, which is a nice little space, but the reality of passers by checking out the yogis unfortunately necessitates a storefront that is mostly frosted glass and hides the life and activity within.

The last corner is a laundromat, which is illuminated into the night, and serves as its own kind of pragmatic beacon and community space. It’s surprisingly nice to chat with people in laundromats, a kind of old school interaction that is dying along with ground floor retail in general.

It’s not obvious from the sidewalk why ground floor retail struggles, but the economics make it pretty clear. It’s difficult for all four storefronts to survive.

A Deeper Dive into the Numbers

Take a 500 square foot corner store space in the North End or Beacon Hill. As a studio it will rent for about $2,000 a month, or $24,000/year, or 48/sf/year, and it’s worth about $400,000, so the taxes are $4,000. That’s approximately eight hundred dollars a square foot, or a very reasonable five cap on the $20k income, slightly less if the landlord actually puts money into the place (most don’t).

If the studio is converted to a condo and occupied by the owner the ~$2,800 residential exemption drops the taxes to $1,200 per year.

For retail to work in that same space (which it was built for!) the taxes are already going to jump from $1,200/$4,000 to $10,000 at that same $400,000 assessment. Whether it’s a net lease or not, a commercial tenant is ultimately paying for those higher taxes.

The business would also have to pay separately for trash collection, even if they generate less trash than a studio apartment.

You would need at least $60/foot, or $30,000 per year, or $2,500 a month for the commercial tenant to be worth it. That’s way higher than your typical neighborhood retail establishment can pay per foot. Class A office space in the Financial District or the Back Bay rents for about $60/foot. Some of the chains (CVS, Chipotle, or similar) will pay more than that for a high volume retail location, but that’s less common and they need more space than these old storefronts can fit. Typically Boston is $25-$60/ft/year for retail.

Consider how many burgers or tortas a hole in the wall counter service place would need to sell to pay that much in rent. Thousands per month? Perhaps more depending on the product? Dense residential blocks can have a few hundred people, so everyone would have to eat there several times a week to support just one restaurant.

People need other services, but there is a limit to how many dry cleaners, laundromats, hardware stores, liquor stores, post offices and boutiques a neighborhood needs.

lintel gone it cannot be converted back easily. Only a better match with the brick and sandblasting could hide it any better. Personal Image.

Even as Boston gains residents overall the number of storefronts isn’t growing much, and it may be even less than at the population bottom in the 80s. A high profile example is all the stores that went out of business in the North End during the Big Dig because people couldn’t get to them easily. More than ten years later many haven’t opened back up, despite more people living and working in Boston. Its too difficult.

Depending on the building and zoning, returning a historic storefront to retail may require a variance for a non-conforming use. This requires public meetings, which are mostly attended by NIMBYs. There may also be fire protection and egress issues, making the reconversion impractical or prohibitively expensive.

It is also worth mentioning that there are many new buildings the city wants to see ground floor retail in but it unfortunately doesn’t work. Developers often struggle to make it pencil out and there can be long vacancies. This is a great example of how planners and urban designers can be detached from the realities of the real estate market. These ground floor retail requirements can make new construction even more unaffordable.

All together, these factors illustrate why there isn’t as much ground floor retail in historic midrise neighborhoods anymore. Each block maybe gets 1 or 2 stores and the historic storefronts are mostly studios. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

How to Foster Ground Floor Retail in Boston

There is no silver bullet for fixing ground floor retail in Boston. It will require a multi-pronged approached and there are many things the city can try.

First, the excessive tax burden on small and historic storefronts should be removed since it can preclude their highest and best use: retail. The commercial tax rate should be dropped from $25 per thousand to the residential $10 per thousand for storefronts under a certain size. The city would not miss out on any revenue since these spaces are already paying the lower rate. A land value tax would also accomplish this. Tax abatements could also be given for historic storefront restorations to encourage architectural improvements.

By-right conversions back to commercial space for certain uses and business hours in existing historic storefronts should be permitted, even far from commercial streets. Loud bars open until 2am are obviously bad neighbors, but hair salons or insurance agencies with a few customers per hour from 8am-7pm are not causing any significant negative externalities and shouldn’t be prevented by NIMBYs. There is no valid health and safety reason not to allow these types of businesses in buildings that used to have them.

Historic storefronts also have lots of untapped potential as incubator spaces for small businesses and startups. A city as entrepreneurial as Boston should be better at promoting this. A “WeWork for storefronts” small office program, focused on turnkey retail and small offices for 1-10 people, would be easy to implement and could be modeled off of the city’s food truck program. Coworking desks cost about $500 per month, so small storefront offices could certainly compete with that.

Online shopping and delivery services like Amazon are increasingly competing with existing retail and are causing negative externalities like traffic and illegal parking. It may make sense to require local deliveries to be made at physical storefronts with loading zones outside and lockers for packages. This would internalize many of these externalities and turn online shopping into something that’s more compatible with urbanism.

Planning for additional density in high-rise neighborhoods adjacent to historic districts can decrease residential rents and also help support more retail in the old storefronts. This essentially replaces a part of the customer base that the historic mid-rise areas lost in the 20th century with additional new neighbors, and it will also allow the balance of residential and commercial space return to normal as the housing crisis abates.

There are undoubtedly many more ways to foster ground floor retail and I’d love to discuss other suggestions. In the post-COVID era, these businesses will need even more help to survive. Ultimately, this issue comes down to what kind of place everyone wants to live in – a boring one with ugly and opaque ground floor spaces, or a vibrant one with nice local businesses – and the city should tailor its policies to meet these goals.

Image by Nishan Bichajian at MIT.